Blazing Passions, seething emotions: 27.4.25

This is one of the quietest, most unassuming books I have ever devoured. It felt as if I was chewing nothing, my teeth grinding air, but in fact I was feasting on a banquet, the richness of which only struck me once I’d left the table. I’d always wanted to explore the fiction of Colm Tóibín, and The Heather Blazing (1992) seemed a good place to start. I was drawn to the vibrant colours of obvious brush strokes on the cover, but I really had no idea the book was about.

It is relentless, one step after another, one man’s life intrinsically caught up in the Irish struggles. He is a character you won’t particularly like, but somehow you have to continue walking in his footsteps. The high court judge is distant from his his family, particularly his wife. When he gently places her in the bath—she has just soiled herself as the result of a stroke—his careful washing of her body is excruciating…I wanted to shout out and I saw myself slam the book onto the bedcovers and yell a fierce “No!” Here is intimacy and longing, inability to empathise and yet deep connection with the natural environment, all told with hypnotic simplicity.

In Wellington I found a copy of The Testament of Mary (2012) by the spare bed in my friends’ comfortable Brooklyn bungalow. Now this topic intrigued me, and I started to read with great interest. Tóibín’s style is similar, but the dense prose somehow rejected me, so I rejected the book. I’m not sure that was a wise thing to do, as I’m sure it would be as intoxicating a read as The Heather Blazing, if only I committed to it. I think I’ll order it from the library.

Serendipity: 24.4.25

A few days in Wellington with my publisher The Cuba Press working on in-line edits and the visuals on The Way to Spell Love. By a wonderful coincidence Mary McCallum and I discover that her father and my mother were in Egypt during WW2 in the former British army camp, El Shatt. Lindsay McCallum was barely a teenager when my mother was a five year old. They had very different experiences of life in the desert: Lindsay was the son of one of the administrators living in the official quarters, men and women separated, and my mother was in one of the many crowded tents that housed refugees from Dalmatia. Estimates put the number at 20,000 to 30,000.

The two would never meet.

The thorough catalogue from a 2007 Croatian exhibition on El Shatt thrills Lindsay when I show it to him at his Paraparaumu home. His memories of the crippling wind that created pink sand storms—the khamsin—and the scorpion guard, thrill me. I’m taking detailed notes for my second book.

Olive harvest: 22.4.25

With all the crazy weather, it’s a race to pick the olives before they are blown off the trees and knocked onto the ground, to be driven over by the cars on the driveway. Every year my mother and I harvest enough to provide a year’s worth of cured olives for the family. Here she is sorting the wizened overripe ones from the juicy plump olives, the green from the black (we bottle these separately).

Olive season marks the descent of winter, and with daylight savings ending and the day plummeting into darkness earlier, all the signs are to hunker down indoors—once the olives have been soaked in water for days, then in brine for weeks, then ladled into jars and covered with some olive oil—with a good book.

Nothing like a little Easter baking…: 18.4.25

I came across a YouTube baking channel and it whet my appetite for brioche for the holiday season—and with winds howling outside and rain driving in at the window joinery, what better way to celebrate being indoors. My first attempt saw different sized buns, but at least each was bursting with a walnut, brown sugar and cinnamon filling—delicious.

My phone was pinging pretty much all afternoon but I focused on the warmth in the kitchen and the rising dough: so much promise, such enticing aromas. My sons were on their property up north a good five hours away, Richard at a memorial service, just Sooty and I snuggling in against cyclone Tam.

Dishes done, baking cooling on the bench, nothing for it but to curl up with my next read, Colm Tóbín’s The Heather Blazing, my first of his oeuvre. I have high hopes.

Tomorrow, Easter Friday, I’m going to try making another sweet bread for Easter, Uskrs, the traditional Croatian Easter recipe sirnica.

Reading for pleasure, reading for pain - Always Remember Your Name: 17.4.25

With a cover photo so beguiling that I couldn’t look away, I collected Always Remember Your Name (2019) from the library hold shelf and started reading before the book had even been issued to me. The subtitle “The Children of Auschwitz” warned me that the material would be difficult…and it was. The fate of the two sisters might have been sealed when they were taken for twins, a favourite of the notorious ‘angel of death’ Josef Mengele. Somehow the sisters survived, in part because their mother, also a survivor, managed to visit the girls in the Kinderblock and sneak them an extra morsel of food. A guard takes pity on them and warns them under no circumstance to step forward when asked “Who wants to see their mama?”; their lovable cousin Sergio could not resist, volunteered, and was taken for experimentation.

My husband comes from the Goldwater family on his mother’s side; this was not just a story for me.

That the sisters Andra and Tatiana Bucci write with such candour makes this an even harder read. It is not literature—and it is translated—but despite its gruesome topic, it’s oddly uplifting. Knowing that the Bucci sisters bear witness at schools and at camp tours somehow makes it a more tolerable read. Only a few short months ago the sisters were filmed in the “Always Remember Your Name” television documentary.

How to keep your man: 15.4.25

Bad Mormon; How to Win Friends and Influence People

Do you ever randomly scroll through the library catalogue and order books you know nothing about? I came across Bad Mormon (2023) while looking for another memoir, and thought to myself “Hmm, Mormonism, interesting” and clicked “Request it”. The cover is subversive: the author airbrushed and perfect (well, she does own a beauty spa), holding The Book of Mormon retitled to include her subversive adjective “Bad”.

I was immediately intrigued by the ritualistic performance of Temple proceedings, and the strangulating yoke that the women and girls of the faith willingly don. Heather Gay whole heartedly embraces her parents’ faith until…she can’t. Ambitious, intelligent, resourceful, she is nevertheless totally convinced that if she is not married to a nice Mormon boy by the time she graduates from college, she’s a failure. And she goes to Brigham Young which, with a 99% population of Mormons, has the largest pool of eligible males from which she could pick.

After missionary work in France (yes, France!) Gay returns to America and meets and falls for Mormon “royalty”, but the marriage quickly flounders once the forbidden sex becomes a duty…keep your man happy! Have lots of babies! Always put on a perfect face!

It’s the perfect face that finally put me off this memoir as it spirals into a messy divorce. Gay becomes famous as one of The Real Housewives of Salt Lake City —she’s the fan favourite—and her story quickly deteriorates into a who’s who of the glamour world. I couldn’t wait for it to end, no matter how much energy the author pumps, like the Botox she promotes, into her narrative.

What a surprise to find, at the back of Dale Carnegie’s world-famous 1936 book How to Win Friends and Influence People (a well-thumbed 1950 Angus and Robertson edition is pictured), a little list of do’s and don’ts to help you keep your husband. Perhaps if Heather Gay been one of the 30,000,000 people who had bought the book, she might still have access to her husband’s private jet. The seven rules for a happy home life (page 216) are probably central tenants of several religions: make up your own mind as to whether or not this is a good book. When I told my son that I was into Carnegie—I’d found his great grandmother’s copy in his room and immediately started to read it—he congratulated me on joining the Carnegie bandwagon. I wasn’t sure if this was a compliment, and I found myself laughing out loud at the great salesman’s advice for domestic felicity. The ten questions wives are asked to pose of themselves just made my day.

Still, after a frazzled phone call to a telecom call centre, I reviewed how I handled the situation. If only I’d used Carnegie’s golden opener “I wonder if you could help me out…” perhaps I’d have ended the call a happier customer.

The things that nurture us (Adolescence, Netflix): 13.4.25

On my morning rounds—feed chickens and collect eggs, gather windfall fruit, pick any blooms about to be annihilated by impending rain, walk to the beach and back—I centre myself for the day. Today I paused, marvelled at the perfection of the egg shells, the size of the feijoas (Mammoth, the best variety), and studied the intense colour in the dahlias that have been flowering for what seems like forever. The sky was broody and the air heavy, and everything felt alive.

I needed to pause. Right now I have friends in every part of the world who are, for one reason or another—and often through no fault of their own—struggling. The demands on them are beyond the reasonable, and I want to support them to the best of my ability. Trauma has a way of creeping up on you so that it takes a toll you can hardly fathom. I experienced this when my father lay in hospital for 60 days unable to eat or walk or talk before he died. I watched him trapped in his body. My forthcoming book The Way to Spell Love came out of this trauma.

A recent harrowing experience was watching Adolescence on Netflix. I implore anyone with schoolchildren to watch it. I binged it, three episodes in a row, then saved the last for the following day as I was in sensory overload. The parallel universe of social media that ensnares its users is laid bare. The viewer is not let off, following the real time action with excruciating fidelity. I wanted to reach into my laptop screen and stroke the face of the mother whose small, bullied teenage son is about to be sentenced for murder. “He’s ours,” his sister tells their parents. He’s ours and we will own him. He is “all of ours”, I realise, as the credits roll and I slump in my seat.

So I pick myself up, go outside, throw the chickens an extra handful of grains as a treat, breathe deeply the fresh air, watch the flax ripple in the breeze. I fill myself up with the good. And I go inside to write.

DON’T TOUCH THIS BOOK! The Vegetarian: 7.4.25

If you want don’t want to lose any sleep, if you want to remain content with your life, and the relationships in it, and if you just want to get on with it, steer clear of Han Kang’s The Vegetarian (2007). The author was awarded the 2024 Nobel Prize in Literature for her ‘intense poetic prose that confronts historical traumas and exposes the fragility of human life’, and previously won the Man Booker in 2016. This book is a big deal. It takes everything you take for granted and rips it apart. One phrase grabbed me by the throat and threatened to strangle me: the protagonist’s sister In-hye realises that the vegetarian sister of the title, Yeong-hye, together with In-hye’s artistically-driven husband, had ‘smashed through all the boundaries’. I can’t tell you how, and I’m trying to put out of my mind what ensues. You don’t want this in your head, trust me.

Or do you?

A bittersweet taste from The Dictionary of Lost Words (Part Two): 5.4.25

Reader, I finished it.

I didn’t want to: I was busy trimming the flax using the obligatory Maruyoshi flax cutter on a beautiful Saturday afternoon with not a cloud in the sky and found myself sneaking back inside, finding my glasses and reading a few pages. It was supposed to be an end-of-the-day treat, something to look forward to, but I just couldn’t stay away.

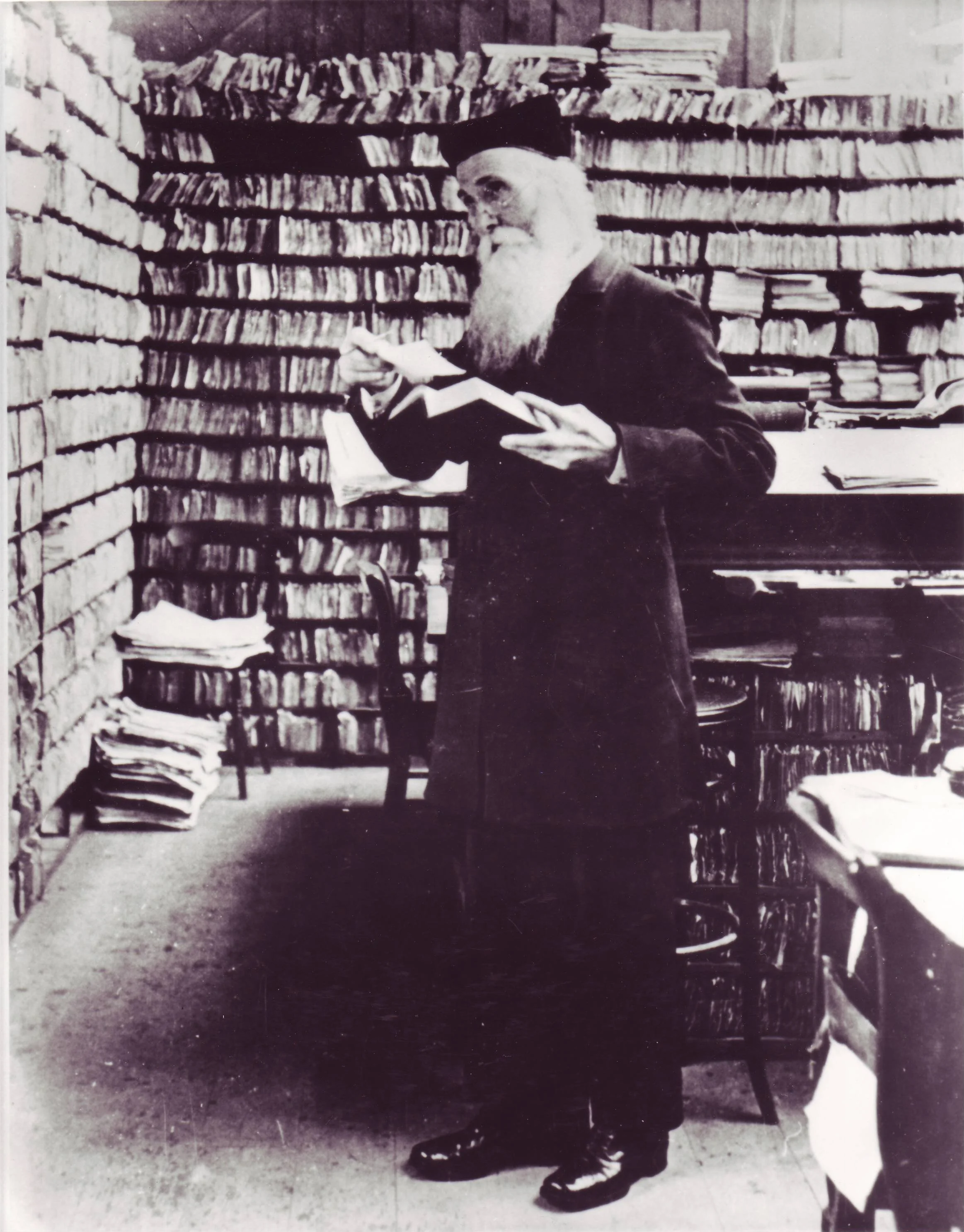

The language was just as simple, the sentences just as hypnotic as the day before, the thrilling idea of little slips of paper holding the meanings of every word in the English language at our disposal still scintillating. In my mind’s eye I kept seeing the beard of James Murray, the dedicated and long-suffering chief editor, growing longer and longer as I read. Some sentences I marked with my own little slip of paper, they were so beautifully crafted. There were couple of moments when I made myself not cry. (I’m not that sort of reader you know, but two books I’ve reviewed recently have shaken me up).

But Williams does an about turn: she romps to her conclusion in a gallop which denies the languorous pace of everything that came before. It’s just not good enough. I’m so disappointed. I needed more. You do too.

Still…if you love language, the tricks of language, and the idea of it constantly evolving, read it anyway. (Part One below)

A book to savour—The Dictionary of Lost Words (Part One): 4.4.25

Today I went to the doctor for a check up—routine blood tests, blood pressure, general wellness—and for the first time I can remember the busy waiting room (and the very long wait) did not bother me. Why? Because I was lost in Pip Williams’ debut The Dictionary of Lost Words (2020). I’m only up to page 130 out of 414, so a third of the way in, and I couldn’t bear it if the novel turned out sabotaging itself. I have such high hopes for this story based on the arduous journey to compiling of the Oxford English Dictionary: it is as if I am floating dreamily on a silky river with not a care in the world, and while I can sense trouble coming (in the story’s arc, in the telling, the structure…), so far it has been averted.

It’s a wonderful diversion from thinking about my manuscript about to arrive from my publisher with the first in-line edits.

I’ll read on, and report when I’m through. Fingers crossed!

Sorting and saving seeds is a lot like editing: 30.3.25

I mentioned tomato seeds from a friend in my last post, and today with drizzle outside hampering my efforts to get into the ground onions (red and brown), shallots, fennel, and as much silverbeet as my garden can accommodate, it’s time to sort my seeds.

I’ve dried five varieties of beans out in the hot sun in my favourite woven tray; then it’s the culling of the damaged, the shrivelled, or the just-not-quite-there seeds that won’t produce what I want next year.

Words are just like bean seeds: some are keepers, and some just have to go. Some combinations you want to save for future projects. There’s just no point keeping the deformed ones, the ones half eaten by bugs. You have to be brutal.

Back home in Whangateau: 29.3.25

A fantastic journey exploring the coast instead of driving straight back home, the beaches each inviting me to take a dip, crystal clear water and the glorious energy of the late summer sun.

Plenty to do on our return collecting windfall golden delicious, with the feijoas in full force, the last of the beans and tomatoes juicy and tempting. Yellow tomatoes? I have a whole garden bed of them from seed a friend gave to me last year: acid free, sumptuous, mild in flavour but startlingly good looking.

And on the north-facing deck a cactus flower totally out of season.

Far North Houhora: 26.3.25

Back up in Houhora to help our sons on their property for a couple of days, me cooking and working on the plantings—weeding, fertilising, rescuing—Richard designing, the four of us making the most of our time together. It was unbearably hot early afternoon so we downed tools, jumped into our togs and headed for Henderson Bay, almost tropical on a day like today.

Refreshed, it was back to work until dark. The Gate Shouse (yes—that’s a word) that Richard architectured for the boys and they have built sits invitingly on the hill overlooking the land, the light showing Viktor working into the night to make the most of the cooler air.

My morning routine: 24.3.25

The first thing I do in the morning is feed the wild cat, Sooty, who’s adopted me—black as tar, slinky, fast and a great ratter. Then it’s the chickens who are now nine years old, too old to be laying, but I can’t imagine putting them in the stock pot. They pick over and stir up the grass clippings and make a great mulch out of all the house scraps, so I’m keeping Chikita (the cheeky one), Snow White (she’s pure white and bossy) and Blackie (submissive, as dark as the cat). There were nine to start with; these are the champions. I then don my walking shoes and take a basket with me down the large front lawn and pick whatever fruit needs eating—scooping up the windfalls which stew beautifully—leaving the basket for me to collect on my way back.

I love my morning ritual walk, my only decision whether to walk along the beach to the boatshed at the bottom of our property first, or after I’ve traversed the bay by road. My hands trail along the nikau and ponga fronds in our bush, my feet lightly gracing our gravel drive and road. Rain does not bother me; my parka is always at the ready around my waist.

By the time I’m back at the house I’m ready for my laptop, my notebooks, the day’s writing.

What I’ve just read—The historical fiction of Hannah Kent: 22.3.25

Burial Rites; The Good People; Devotion

I’m going to do what I don’t do: review three books by the same author. (“Okaaayyy,” I hear you interject, “you mentioned two of Febos’s books in your last reading post. What’s one more?” Let me tell you, reader, one more is much, much more. Two is being engaged. Three is marriage, mortgage, kids, the works.

I can’t recall which reading rabbit hole led me to Kent, but it was Burial Rites (2013) that attracted me because of the Icelandic setting. A close friend’s son had become enamoured of the country while on a 360 International study year and, when my friend WhatsApped me daily images of impossibly wild and icy landscapes while visiting him, I found myself under its thrall too. Ah, yes, now I remember…Kent’s forthcoming memoir Always Home, Always Homesick intrigued me: the publisher’s selling pitch was that it explained the genesis of BR. Now, I am an impassioned reader, and I will often throw a book across the floor if I think it has ended badly, or sloppily. (I’ll throw it carefully, so as not to damage the spine. I’m a book lover, come on!) . When I finished BR, I burst into sobs of anguish. Richard was just rowing back from an explore ashore at Rocky Bay, Waiheke (gorgeous island, fabulous to sail around) and I felt foolish that he was witnessing my emotional meltdown in response to a novel. But it is not just a story set in 1829, that’s the rub. It’s true. And the ending is unbearable. And I can’t say anything more. Except that if you don’t read it, you must be dead.

Next was Devotion (2021), even though it is Kent’s third novel. I liked the Prussian/Australian canvas, and the promise of a six-month harrowing sea journey with all the sacrifices that entailed in the 1830s. I’d been on the HMS Victory in Portsmouth and found twenty minutes below deck impossibly claustrophobic. Six months…? Devotion didn’t have the urgency of BR but its originality was startling and wonderful. A spacious book.

Last was The Good People (2016) set in Ireland in 1825. I was attracted to this novel less than the other two, but I’d found Kent’s style so easy to digest, fluid and lyrical, that I wanted to see if she could sustain it over three novels. She can, and she did. Much denser, GP is also inspired by a true incident, that of infanticide—an attempt to ‘put the fairy’ out of a child—and is a compelling account of belief, both religious and folky. Faith features in all three of these novels: GP was the one that I had to repeatedly sneak back to during my writing day, telling myself that my snatched reading was a well-deserved break. That’s testament to how engrossed I was in the parallel worlds, the all-suffering tenant farmers, and the “good people” of the title.

Three novels in two days. Of course I’m going to read Kent’s memoir the minute I get my hands on it. Watch out for my review. I’ve Googled her and read her posts on Instagram and done everything a devout reader does these days. Go do it yourself.

Model of house, Stari Grad, Croatia: 21.3.25

This little house made of the stone from my mother’s village is typical. A street-level lower floor is cool in summer, warm in winter with a fire in the corner, and the stairs lead up to the second floor. In my mother’s house there is a pergola covered in a vine but the bees go mad for it and sticky pollen drops onto the stone terrace—it needs washing every day. The stones have been in place for hundreds of years, and will stay for hundreds more. When I walk up the narrow stairway leading to the upstairs bedroom I have to steady myself against the wall so as not to topple backwards. I imagine my mother as a girl skipping up these stairs, her grandmother who lived in the house clinging to the wall as I do.

In the novel I am writing now, Vinka runs to this house in the dark each night from her parents’ house a street away. She hates that journey, but it is her duty to keep her grandmother company in the night. I’m writing of her reluctance and her commitment, her skittishness and spirit. It is not my mother who is my character, but I am borrowing some traits in her I know so well. As I craft Vinka’s actions in my story—and the consequences of them—I wonder at how fiction and real life intersect. Much of what I am writing I am fabricating, watching that young goat girl scamper around the village in my mind, imagining what she might do next.

I’m amazed how often my mother says, when I read bits of the book in progress to her, “That’s what it was like. Exactly.” It’s as if I am tapping into knowledge that I cannot possibly have. My characters are writing their stories—and their fates—from some deeper well.

What I’m reading: 18.3.25

Abandon Me; Girlhood; The Instrumentalist; Didion & Babitz; The Outrun

Allow me to introduce you to the celebrated Melissa Febos, one of the most original and confronting authors I have read in years—perhaps ever. Febos is fearless, and you need to be a bit fearless too when you pick up any one of her books. My first taste of her electrifying prose was in the stripped-bare memoir Abandon Me (2017), a book I picked up and put down again repeatedly, showing myself how uncomfortable I was becoming with Febos’s mirror-reflection reveals. I did the same with the essay/stories in the award-winning Girlhood (2021). There is not much I can say but go get one of these books and confront yourself, on so many levels. Not really fun, but oh so worth the while.

I loved The Instrumentalist (2024). You’ll love this book too. If you love the music of Vivaldi…well, that’s another matter. Anyone who has fallen under the spell the city Venice weaves so effortlessly will devour Constable’s novel, forgiving the occasional clunkiness such as the far-fetched foray into the outside world the orphan musician protagonist Anna Maria della Pieta makes. Wait…did I mention the orphanage is famed for its superbly talented and disciplined musicians for whom a place in the stellar line-up of the Figlie del Coro orchestra almost guaranteed that they would not be married off to the oldest richest bidder? The visiting maestro who does more than instruct? The frequent postings of unwanted babies through a too-small hole in the orphanage wall? See…you have to read this book. Light, entertaining, historically revisionist, and very satisfying. Based on a true story.

Ah, the Didion/Babitz feud. Or was it? Lili Anolik has committed the ultimate sin of falling in love with her subject, Eve Babitz, writing two books, Hollywood’s Eve (a play on a title by Babitz Eve’s Hollywood), and this one, Didion & Babitz (2024). Babitz wrote gossip-fuelled observations about LA like no other, all autobiographical. Joan Didion wrote pithy observations about the other coast, largely autobiographical. The two authors were in and out of each other’s lives, each other’s pockets. This is quite a ride: strap yourself in and be prepared for turbulence.

Another scraping-the-bottom-of-the-barrel confession guaranteed to uplift the reader: thank God that’s not me! I’d never go that far off the rails! I’ve got far more control!…What happens when you go off the rails to the degree that Amy Liptrot has done is that when you locate the tracks again, the ride once you manage to jump back on them is so much more beautiful than when you fell off. Books like The Outrun (2015) almost make me want to succumb to excess—alcohol in Liptrot’s case—so that my recovery can be celebrated in a bestselling memoir. A read of extraordinary beauty if you can bear to experience the lows along the way. And if you are a nature lover and celebrate the deserted wilds, such as in this Orkney Isles setting, this book will captivate you. It deservedly won awards for both first memoir and nature writing.

Warkworth A & P Lifestyle Show: 16.3.25

Growing up in Pukekohe one of the highlights for me was the annual A & P show at the height of summer. I’d head straight to animal pens and ogle the enormous cattle, wondering what it took to win a red ribbon. I’d scratch the pigs behind the ears, marvel at the evident intelligence in the dog trials. There was always a wildness about the show with gaggles of teenagers letting loose, the whoosh of fairground rides that scared me.

Yesterday the Warkworth show was more food stalls and face painting, but the free entry for under fives—and free rides— was a brilliant strategy. There was something in the atmosphere, something simple and uniting—so many happy faces, so much politeness, consideration. A giant bull lying on his side was nonplussed by it all and I thought he could be the poster boy for mindfulness despite the record crowds and the 28 degree heat.

But it is always the woodchopping that impresses. Partly due to the sweat and tension the men exuded, partly due to the essential shade of the nearby bank with its mature trees, there was a growing crowd supporting the axemen. And woman: a lone female braved the competition; we all clapped heartily. I chatted with a man cheering on his three grandsons competing against each other. When the springboard competition was on, the crowd was silent, willing the axemen not to fall.

My grandfather Nono, Stari Grad, Croatia: 15.3.25

This is my mother’s father, a quiet gentle man who never raised his voice, just lifted his head to nod an approving yes, or shake it to one side to show his displeasure. I first met Nono and my grandmother Nona when I was nearly twelve years old: the moment I saw the delight on his face when he held me in his arms, then held me at arms' length so he could study this almost-teen who was his granddaughter from the other side of the world, he was special to me.

I went back many times to stay with him and my nona, and I delighted in helping him on the family lands to the best of my ability. When I was flown to the newly-formed Croatia in 1994 by Television New Zealand to narrate and participate in a documentary on Croatian identity in both the country of my birth, and that of my mother’s, Nono was a natural in front of the camera.

In his orchard he lightly put his arm around my shoulders while the camera rolled, and I leant in to him.

When I went back to the village after he was gone, I found his hat still sitting on the bench we once thought of as his.

Grape Harvest (Jematva), Stari Grad Croatia: 13.3.25

My cousin Helena and I were willing pickers for our grandfather, Nono. Each morning at 4am Nono would stand under the window of the room we shared and softly call, only once, “Ni-na”. We would be up and out of bed quickly, dressing in the dark and scrambling down the old stone stairs to the cellar kitchen our mothers ate their meals in when they were children. Under a single bulb Nono would drink his coffee while we dipped crusts of yesterday’s bread smothered in delicious honey into ours.

We walked to the vineyards which are in the Stari Grad plain, now a UNESCO World Heritage site: grapes have been grown here for over 2400 years. Nono rode Hassan the donkey with bags roped to the saddle.

Here we bend over to pick the grapes which are very low, and soon our backs are giving in—but we will not give up. We both want our grandfather to be proud of us. We pick until the sun burns too brightly and Nono nods to us to stop.

Nono tended Hassan’s saddle with care.

I return, contemplative, and sit among the vines in winter alone twenty years on. Well, not so alone…I was pregnant with Alvaro, without knowing it.

In 2024 Helena and I sit in our favourite coffee bar while my two sons do the picking.

Whangateau—paradise between Matakana and Leigh: 12.3.25

When I’m not at the end of our dining table closest to the french doors with the fabulous view, I’m out on the property planting, tidying, watering, pruning, chopping, mulching, feeding, and any number of other rural tasks that can easily fill a day. A writer sits at their keyboard for most of their working hours—a solitary, quiet, potentially lonely time—so breaks out in the sun and wind and (please, PLEASE we need some right now) rain are a must. At this time of year my favourite pastime is stacking the wood that Richard chainsaws from the branches fallen on our property. With an extensive range of mature trees, we have no shortage of sawing and tidying each autumn.

So Saturday was a very happy day for me: we assessed the mature oak half way up our drive and cut the limbs that were struggling after this taxing dry summer. There was more wood than I had hoped: my stack now has a second row. I’m mixing large logs and smaller, thinner ones so that when we race out to the shed in the middle of winter we can grab a handful and there will be starter and more serious logs in the same basket to burn. The beauty of the drying wood is so pleasing I could just stand and look at it…but back to the keyboard!

Far North, Houhora (almost the top of New Zealand): 11.3.25

Our two sons are developing a property 40 minutes by car from Cape Reinga, one of the most spiritual places in the country, known as “Te Rerenga Wairua” or '“the leaping place of spirits”. The land in Houhora is also a magical place of beginnings and endings: when Viktor and Alvaro found the five hectares, little did we as a family know how much we were each to contribute to the project. Richard designs for them, their “architect on tap”, while I cook and plant and garden and help them with publicity.

The row of bamboo is a fabulous shelter belt, but the pines are now all gone and replaced with natives. Every bit of wood on the property has become a floorboard or a wall lining, the scraps firewood. But here Vitkor and I are just wandering over the land, discovering the extent of the waterways and the watermelon-picking crates left by the previous owners. I had my eye on these for compost bins.

Houhora has become a settling place for me where I go to help the boys but also retreat into myself to think and write. There is something so primal in the land that time seems to move barely at all, and the days merge into nights with skies so full of stars they are like a blanket tucking me in so that I can dream about my next piece of writing.

Houhora Far North land before development

Grape Harvest, Matakana New Zealand: 10.3.25

It’s been so hot and dry this summer the posts between the vines in my brother’s vineyard in Matakana are moving in the baked earth as we pick. There is a team of nine of us who brave the heat and the wasps—not that many this year, thank goodness—to pick the Syrah. The berries are delicious. Our pruners are thin and dangerous, our hands protected by black plastic gloves that soon render them bathed in sweat.

It makes me think of the sumptuous Palomino that we picked in our family vineyard in Pukekohe, a box nearly filled by two or three bunches. Here I am with my mother celebrating the harvest which my father acknowledged by taking us all for the first time to Yugoslavia. I am barely capable of holding up the bunches they are so heavy, the berries perfectly ripe, firm, sweet. It is 1973. I am about to fly around the world and meet my mother’s family.

Fast forward to 1985. The vines are about to be pulled out, the vineyard over. There is a glut of grapes in New Zealand. I have just returned from my OE. My mother and I hold the same variety for the last time. Our harvest is bittersweet.

Thirty years later my mother, now 86, is still picking grapes.

Entrance to the Stari Grad harbour, Croatia: 9.3.25

Every time I take the ferry from mainland Split to my mother’s village Stari Grad I have to leave the saloon and lean over the rails to greet the harbour. I have taken this trip many, many times—every year apart from the Covid years when we were all homebound—and I never fail to be moved beyond words as the village draws near. In my head I am reversing my mother’s journey when she farewelled her own mother and father, her sister and two brothers, not to see them for 15 years. What must she have gone through I ask myself each time I hear the ferry’s horn blasting it's sorrowful departure, and how must if have felt when she made the first trip back married with three children, two of them teenagers.

Here I am 40 years ago imagining my mother’s emotional turmoil. It has haunted me the forty years since. In ‘The Goat Girl’, the novel based on my mother’s life which I am now working on—in earnest while my publisher edits my first book The Way to Spell Love— I’m trying to capture the yearning I feel for my mother’s village. I become someone else in this village: I talk louder, I gesticulate more freely, I laugh at silly things and I feel unencumbered. It is as if I am already slipping into my mother’s childhood skin as I disembark the ferry at the small, chaotic port.

Photo selection for The Way to Spell Love: 8.3.25

Which images to keep, which to discard?

I aimed to choose around 40, spanning more than 70 years, with those to be culled to about 30. As I trawled through the large plastic storage bin in which I had collected all my photographs and half-filled photo albums—and those awful small plastic photo books that fell apart as you flipped through them—the task seemed impossible. So many images begged questions, and as I looked closer, I saw details that I’d missed time and time again.

Did my mother struggle to cut the straps of her embossed paisley cocktail dress evenly? She’d barely learned how to sew, my father driving her to lessons as she hadn’t yet mastered driving—nor the language. Only a handful of years earlier she was running barefoot on the cobbles of her village in a hand-me-down, the sumptuous fabric of this dress a dream. And Aunty Ivy, her large bust gripped by her satin sheath dress with the extravagant rose sewed above her left breast…what did she think of her younger, naive new sister-in-law?

They smile easily at the camera, my mother taller, slimmer, younger, more beautiful than my aunt. I loved them both. I wanted them both to love me back.

This photo didn’t make the cut.

My next book—set in Stari Grad, Croatia: 6.3.25

My cousin Helena sent me a video this morning of an amazing old custom from my mother’s village in Croatia. It’s called Jure Karnevol, a figure put on trial for everything has gone wrong over the past year—the fall guy. A procession through the village streets is noisy with lots of yelling and bumping, clanging of bells, banging of pots, and the shrill trill of whistles as the people in it drive out the evil from the village and the houses. My mother’s village calls it “Procesija Lancuni” which means “Procession of the sheets”. Everyone is wrapped in a white sheet (and you can bet they are spotlessly clean!) Check out the Dalmacija Danas video here too.

I will have to put this wonderfully pagan annual event in my next book. It has the working title “The Goat Girl” and it’s based on my mother’s childhood in Stari Grad and her wartime refugee experiences. How many more old practices are there like this one that I will discover? When I asked my mother she said she’d never been in a Lacuni procession: it was suppressed in Tito’s Yugoslavia.

Since I posted this, Helena told me Lancuni has appeared on Croatian TV.

Procesija Lancuni, Stari Grad Croatia

What I’m reading: 5.3.25

Cher the Memoir; Life Hacks From The Buddha; The Empathy Exams; Stoner

Just finished romping through the first part of the very dramatic and colourful life in Cher the Memoir: Part One (2024). Had to Google “I Got You Babe” to hear how clonky Sonny’s voice really was. It was startling to see young Cher so prepossessed. How many memoirs have I read where the author laments a missing mother, a family separation? Fun, troublesome, an easy read. I’m waiting for Part Two.

Dr Tony Fernando also calls on his life experience to illustrate the principles he explores in Life Hacks From The Buddha (2024). Catchy title, easy tips to follow, very relatable. Tony was my guest at the University of Auckland where he spoke to first year students on how to keep it together—he made a difference. Read this book!

You might think a book with a tile like The Empathy Exams (2014) would be taxing, and it is, but it takes its toll on you in surprising ways. Author Leslie Jamison writes gob-smackingly moving prose that shocks and instructs alternately in these essays on topics ranging from her experience as a medical actor to how she navigates the abysmal realities of narcotic-soaked central America. Come to this book ready to be humbled in so many ways. Much more than memoir.

A Vintage Classic, John Williams’ Stoner (1965) appealed as it is set in the University of Missouri English Department. Spanning the life of the lecturer William Stoner, and two world wars and the Great Depression along the way, this quiet story is in turns depressing and uplifting, at once joyous and tragic. Based on Williams’ lifetime dedication to lecturing, The New York Times called it “perfect”, promising that “it takes your breath away.” It does. Prepare to be breathless.

The Road Back: 4.3.25

This still from the short film The Road Back, adapted from one of Amelia Batistich’s most beloved—and more disturbing—short stories of the same name, shows three generations of my family. The lead village woman facing the camera is my mother who celebrates 86 years today; the small child with the frilly white hat is my elder son Viktor, now 30; and I am holding him among the group of women turning their back on the film’s protagonist, Vinka. Vinka is holding a small mirror which she carries with her everywhere so that she can see her reflection and imagine it is another woman offering her companionship. The film portrays the trauma of migration; working on it with my mother and son was a rewarding experience. My mother was once that migrant who yearned to return to Yugoslavia, but could not. Here she shakes her head at Vinka, telling her, and herself, that there is no going back.

Anniversary: 21.2.25

Seventeen years ago today—at this exact time, 7 pm—I looked up at my father who was lying in a hospital-care bed and noticed his hand changing colour. The creep of blue along his fingers gave his hand a surreal quality. I stared at this horror for what seemed like an eternity, but it must have been only a few seconds before I pressed the ‘Nurse Call’ button. I needed reassurance. But I didn’t receive it. My father was gone twenty minutes later.

I wrote about his death and the fallout from it in my family. It took many years to shape the stories that were a part of his life, his dying, and what he left behind. The Way to Spell Love is that book. There are so many things I would do differently if I had my time with my father over again, but also things that I would not change. Some things happen for a reason only time can reveal to us. Some should never happen in the first place.

Our Summer Holiday: 15.2.25

With wind most of the summer, Richard and I took the opportunity of a few fine, calm days to go sailing on Starlight, our beloved Townson, around Waiheke Island. Here we are anchored off West Bay on a scorching still day. I took a pile of books with me as usual, read most of them, rejected a few. The sea was crystal clear, buoyant, joyous. It was not easy heading back to Westhaven marina in the city, but it’s always comforting to drive back up to our farm 45 minutes on SH1.

My Big Year: 11.2.25

2025 is my big year: my first book The Way to Spell Love is due for publication by Cuba Press in November.

I am busy trying not to repeatedly edit my manuscript—Mary McCallum has told me that it’s hands off until the official editing process begins in April—but it’s hard to put down, and impossible to stay away from the keyboard.

I’ve just changed the title: it was “The Best Way to Spell Love”, but as you will read in the epilogue, that was not to be.

Watch as we edit and polish my memoir ready for you to read the end of the year!